PROF. JENKINS: Professors should check their politics at the door

I believe we as professors should speak the truth, as much as we can know it, for the sake of speaking truth, not to counter a narrative.

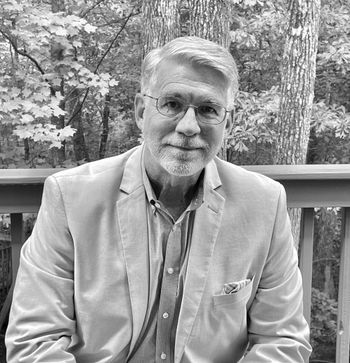

Rob Jenkins is a Higher Education Fellow with Campus Reform and a tenured associate professor of English at Georgia State University - Perimeter College. The opinions expressed here are his own and not those of his employer.

Hardly a week goes by without leftist professors and administrators beclowning themselves by endorsing Hamas or pushing “transgender” nonsense or singing the praises of DEI. Talk to any conservative college student and you’ll hear horror stories about the latest attempts to promote these vile and discredited ideologies in the classroom and elsewhere.

All of which raises the question: Should conservative professors—the few of us who exist—“fight fire with fire,” so to speak, by advocating for our own beliefs in the classroom as a way of offsetting the constant barrage of leftwing propaganda?

I say no, even as I acknowledge that a growing number of higher ed commentators on the right are advocating for exactly that. Their basic argument is that if students hear nothing but lies from their leftist professors, and those of us who know better don’t tell them the truth when we have the opportunity, they will simply come to believe the lies. There will be no pushback at all against the leftwing narrative unless conservative professors are the ones pushing back.

While I respect that argument and believe it has some merit, I ultimately reject it. I don’t believe education should be about indoctrination at all—influencing students toward one set of political beliefs or another. I believe we as professors should speak the truth, as much as we can know it, for the sake of speaking truth, not to counter a narrative.

[RELATED: PROF. JENKINS: Can we reform the professoriate?]

There are also times when I need to be able to play Devil’s advocate—to take the opposing side in a classroom debate even when it’s not a position I happen to agree with. Sometimes that’s the best way to make a point, help students see the weakness of an argument, and teach them how to strengthen their own arguments. If students are too well acquainted with my political views, that can be a difficult if not impossible task.

For that reason and others, I would rather my students not know exactly where I stand, politically. If one day they think I might be a conservative and the next day they’re wondering if I’m a liberal—and by the end of the semester they still have no idea--that, to me, is the ideal situation.

I also heartily endorse the old cliché, “We should be teaching students to think, not teaching them what to think.” That’s why I focus so much on critical thinking, both in my classroom and in my book, Think Better, Write Better.

[RELATED: PROF. JENKINS: ‘Social justice’ is injustice by another name]

Note that when I say, “critical thinking,” I mean it in the old-fashioned sense—not the modern sense, which has come to refer almost exclusively to Marxist critical theory. I explored this distinction in depth a couple of years ago, but allow me to reiterate for this discussion that, traditionally, critical thinking has entailed asking questions, formulating and testing hypotheses, and cultivating objectivity by analyzing differing points of view.

Essentially, my position is this: If what I believe about the world is true, and what leftists believe is generally false, then the first thing I need to do is encourage my students to seek truth, rather than just parroting slogans and adopting the current fashionable attitudes. The second thing I need to do is teach them how to discern truth using their rational faculties. If they can do that, they should be able to arrive at the correct conclusions most of the time.

The best part is, they will have come to those conclusions on their own, which means they are more likely to embrace them, internalize them, and live by them. They won’t just be temporarily trying on some position for size simply because a professor told them they should, which is what far too many students do already. That’s what has gotten us into this situation to begin with.

In short, I believe truth is self-evident, once people break free of their conditioned responses and learn to see it. My job is to help students do that—not condition them with another set of responses, even if I believe those to be more correct.

Editorials and op-eds reflect the opinion of the authors and not necessarily that of Campus Reform or the Leadership Institute.